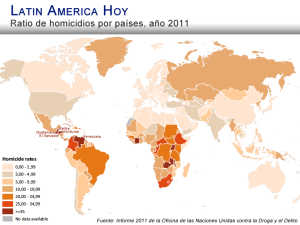

crimen en el ano 2011:

Donde los gobiernos permiten tener armas hay mas homicidios – caso cerrado!

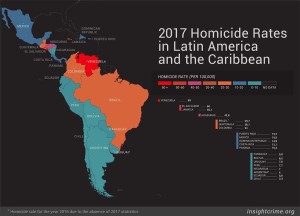

crimen en el ano 2017:

mas sobre este tema encuentra en la pagina red «insight crime»

Honduras Profile

One of the poorest countries in Latin America, Honduras is now also among the region’s most violent and crime-ridden countries. This is due in part to its role as a strategically important transit nation for the transnational drug trade, as well as macroeconomic shifts, endemic poverty, corruption and political turmoil. Estimates vary, but between 140 and 300 tons of cocaine are believed to pass through the country each year.

In recent years, transnational criminal groups, particularly Mexican cartels, have expanded their presence in Honduras. The 2009 coup that ousted President Manuel Zelaya and caused international outrage also exacerbated instability in the country. Colombian drug trafficking gangs changed their routes to Honduras just days after the coup and turned it into the principal point for handing cocaine over to Mexican cartels.

However, it is a series of powerful local groups, connected to political and economic elites, who manage most of the underworld activities in the country. They have deeply penetrated the Honduran police, which is one of the most corrupt and mistrusted police forces in Latin America.

A large and increasingly sophisticated group of street gangs also plagues this country. Citizens and businesses face the threat of extortion and kidnapping, and Honduras’ investigative capacity is very weak.

The Honduran government has increasingly turned to the military to enforce the rule of law, sparking concern from many human rights groups. The judicial system is afflicted by political interference, corruption, and a lack of capacity and transparency.

Geography

Honduras has a vast, largely unpopulated territory, access to two oceans, and three borders that would make it difficult for any government to control. The country is just slightly larger than the US state of Tennessee, but has a small, aging and outdated military and police structure. Large stretches of coastline, especially the northeastern area near the border with Nicaragua, are prime landing spots for drug trafficking organizations.

A large, underemployed region, hit hard by overfishing and other shifts in the economic situation, provides a ready-made workforce. Expansive and sparsely populated territories to the east also provide landing and transit zones for drug traffickers.

Gangs are concentrated in the largest urban areas, while the unmanned borders with Guatemala are the country’s most important crossing points for illicit goods.

History

Honduras has never been a particularly stable country, and in recent decades, war and major macro-economic shifts have left it vulnerable to organized crime. The country’s proximity to warring nations in Central America has long made it a prime spot for the transit of illegal weapons, contraband and drugs. The government’s decision to become involved in regional free trade agreements also displaced numerous traditional economic motors at a time when large drug traffickers were changing trafficking routes.

The country’s first premier international drug trafficker was a man named Juan Ramón Matta Ballesteros. Matta’s beginnings stretch back to the early 1970s when, after escaping custody in the United States for drug trafficking crimes, he made his way to Mexico. In Mexico, Matta liaised with what would become the Guadalajara Cartel, a loosely knit group of transporters who were moving Mexican drugs to the United States and starting to connect with Colombians interested in transporting cocaine to the world’s largest drug market.

Matta consolidated his power in the Honduran underworld with the 1977 murder of Mario and Meri Ferrari, smugglers with whom he had previously worked. Matta then established what can be described as the Honduran bridge, linking what would become the Medellín Cartel and the Guadalajara Cartel. His power inside Honduras reached the highest levels. Rumors suggest that he even financed a military coup in 1978.

Matta’s connections to the military remained intact even after the junta abdicated power to a democratically elected government in 1981. He continued to expand operations, moving between Honduras, Mexico and Colombia. After the Guadalajara Cartel tortured and killed Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) agent Enrique Camarena in 1985, Matta became one of the most wanted men in the region. He was captured in Colombia the following year, but bribed his way out of jail.

Matta then went back to Honduras, where he bought off the government and appeared safe from prosecution until 1988, when US Marshals showed up at his house, took him captive and couriered him back to the United States to face trial for the death of Camarena. Hondurans were furious and burned the US consulate. Matta was later convicted of kidnapping and is currently serving his sentence in a US federal prison.

Throughout the 1980s, Honduras was used as a trampoline for the movement of all types of illicit goods, from drugs to weapons to contraband. The US government, more concerned with fighting what it considered a burgeoning communist threat in the region, even contracted Matta’s air fleet to get aid and weapons to Nicaragua’s Contras, who were fighting the Sandinista government at the time. Even after the armed conflicts ended, the contraband routes remained prevalent.

In the early 2000s, the country experienced a new surge in drug trafficking and illicit activity. As drug trafficking organizations in Mexico became the principal operators and gained more control of the distribution chain, Central America’s importance rose. Local transportista groups emerged, the most important of which were the Cachiros in the northeastern province of Colón, and the Valles in the Copán province. These organizations worked with other Hondurans such as José Natividad “Chepe” Luna and José Miguel “Chepe” Handal, as well as international traffickers such as the Sinaloa Cartel.

In recent years, Honduras has seen its homicide rate skyrocket partly because of this increased criminal activity, though violence has declined from its peak in 2011. Economic inequality and lack of opportunity for young people have contributed to the spread of street gangs, which are the primary drivers of violence. Like Guatemala and El Salvador, Honduras is home to thousands of street gang members, most notably affiliated with the Barrio 18 and MS13. These gangs — most active in the capital of Tegucigalpa, but present throughout the country — often exert influence over entire neighborhoods, imposing their own order, demanding extortion payments from businesses and residents, and running local drug trafficking and kidnapping rings. According to the UNODC, as of 2010, there were estimated to be 36,000 gang members in Honduras.

Since 2003, Honduras has pursued an “iron fist” (“mano dura”) strategy against gangs, handing down harsh punishments for alleged gang members on the basis of their appearance alone; for example, for having gang-affiliated tattoos. These policies, which did not address the root causes of gang membership or provide rehabilitation for gang members, have led to an increase in the prison population and burdened Honduras’ already stumbling penal system.

Another contributor to rising violence and criminality is the country’s political turmoil. In response to former President Manuel Zelaya’s decision to call a referendum on establishing a Constituent Assembly for the preparation of a new Constitution, he was detained by the armed forces on June 28, 2009 and exiled to Costa Rica. Criminal groups took advantage of the turmoil in the wake of the coup, which shifted state security forces’ attention away from crime and toward maintaining political stability.

The United States designated Honduras a major drug transit country for the first time in September 2010. Since then, drug trafficking activities have intensified in Honduras and other countries in Central America, driven in part by a boom in Andean cocaine production. Drug flights, particularly from Venezuela, have also been a source of concern in the past, though Honduran officials say that they have managed to eliminate this issue.

Honduras has cooperated closely with the United States on combating organized crime in recent years. In May 2014, Carlos “El Negro” Lobo became the first Honduran drug trafficker to be extradited to the United States. A number of other high-profile criminal suspects have subsequently been extradited, and several have provided information to US authorities as part of plea agreements.

This cooperation has at times sparked controversy, as was the case in 2012, when several anti-drug raids conducted with assistance from US law enforcement saw allegedly unjustified uses of deadly force, including one incident in which a number of civilians were killed.

Criminal Groups

Arrests in recent years have taken down top leaders of several of the most important criminal organizations in Honduras. The Cachiros drug trafficking group, for instance, has seen its leadership captured and extradited to the United States, where former Cachiros leader Devis Leonel Rivera Maradiaga has provided explosive testimony alleging that he operated with the assistance or complicity of various political and economic elites.

The Valles drug trafficking organization, which allegedly shipped tons of cocaine each month to the United States, has also been nearly entirely dismantled, with many members sent to face trial in US courts.

Sinilarly, the United States was involved in targeting the Atlantic Cartel, whose leader Wilter Neptalí Blanco Ruíz was arrested in Costa Rica in November 2016 and later reached a plea agreement with US prosecutors in July 2017.

In addition to drug trafficking groups, Honduras is also home to gangs. The two largest, MS13 and Barrio 18, operate mainly in urban areas, and subsist largely through extortion and local drug dealing. While there are indications that the MS13 may be increasingly moving toward becoming a transnational criminal organization, evidence suggests that the Barrio 18 continues to operate on a largely local level.

Various groups and individuals in Honduras also engage in trafficking firearms both into and within the country.

Security Forces

Honduras’ National Police is housed under the Security Ministry. The force had less than 14,000 officers in 2016, with plans to nearly double that numbers to approximately 26,000 by 2022. Within the National Police, there are three main divisions: the National Preventive Police (Policía Nacional Preventiva), which operates in cities throughout Honduras to prevent crime and ensure public safety; the Municipal Police (Policía Municipal), whose forces are coordinated at the central level but organized by local authorities; and the National Bureau for Criminal Investigation (Dirección Nacional de Investigación Criminal – DNIC), which is linked to the Attorney General’s Office and is tasked with investigations into criminal procedures.

Honduras’ police force is one of the most corrupt in the region. In addition to demanding bribes, passing information to criminal groups, and allowing drug shipments to pass unchecked, some Honduran police have reportedly participated in, and even directed, violent criminal operations.

Since 2011, the country has been engaged in a police reform process aimed at weeding out corrupt elements by administering confidence tests such as polygraphs and drug tests. For years this process saw few concrete results, but in early 2016, the government created a police purge commission following revelations that top-ranking members of the police had participated in the 2009 murder of Honduras’ anti-drug czar. The commission has reviewed hundreds of high-ranking officials, with many leaving the force. Its mandate was renewed in early 2017 to last for at least one more year.

The government has increasingly turned to using the military in a policing role. In November 2011, the government issued an emergency decree, which has since been renewed, that granted the military policing powers. And in 2013 congress approved a bill to create a new elite military police unit to fight organized crime. Under President Juan Orlando Hernández, elected in 2014, thousands of military police have been deployed to combat crime.

Honduras’ military, which is housed under the National Defense Ministry (Secretaria de Defensa Nacional), has 12,000 active personnel, mostly concentrated in its ground forces. Under Honduras’ constitution, the military is able to cooperate with public security institutions, at the behest of the Security Ministry, to combat drug trafficking, arms trafficking and terrorism. The country spent around 1.6 percent of its gross domestic product on its military in 2015 — a total of $325 million.

The military is a powerful political and economic force within Honduras, and many human rights defenders have questioned the growing power of the Honduran military and its increasing involvement in public safety, Some have argued that the decision to grant police powers to the military violates the separation between military and police roles protected in the constitution.

Judicial System

Honduras has a civic law system. Constitutionally, Honduras’ judiciary is independent, although in practice it is subject to pressure from the executive branch and from congress. The highest court is the Supreme Court of Justice (Corte Supreme de Justicia), which has 15 judges elected for seven-year terms by the congress. There is no Constitutional Court, with the Supreme Court instead housing a constitutional chamber. The Supreme Court has final appellate jurisdiction. The judicial branch also includes a Court of Appeals and other lower and specialized courts.

The Public Ministry (Ministerio Publico – MP) is an independent body charged with prosecuting crimes, defending the interests of Honduran society, and ensuring that laws and the constitution are properly protected and enforced. The Attorney General’s Office (Fiscalía) is housed under this ministry. In 2010, the Justice and Human Rights Secretariat (Secretaria de Justicia y Derechos Humanos – SJDH) was created to hold the executive branch accountable on issues of justice and human rights. The human rights ombudsman (Comisionado Nacional de los Derechos Humanos – CONADEH) is the independent body responsible for promoting and protecting human rights in Honduras.

Prisons

Honduras’ overburdened prison system, administered by the National Directorate of Special Preventive Services (Dirección Nacional de Servicios Especiales Preventivos – DNSEP), holds 17,000 inmates, well over its 8,130-person capacity. The DNSEP is housed under the Security Ministry (Secretaria de Seguridad) and is run by the National Police (Policía Nacional de Honduras). Suspects often face long pretrial detention, abuse and denial of due process. There have been several incidents of riots and killings in the country’s overcrowded, underfunded penitentiaries. They have also become centers of criminal activity for gangs, due to the lack of control that authorities have in many facilities.

Comments are closed.

[…] InSight Crime, a Washington, D.C.-based foundation that tracks organized crime, reported in a 2014 Executive Summary that “a series of powerful local groups, connected to political and economic elites … manage […]